Successive research has demonstrated that young people are more vulnerable than most in terms of their ability to understand and use the law. Legal needs surveys show that those starting the transition into the adult world are at high risk of experiencing common legal problems. However, disadvantaged young people are the least likely age group to obtain the law-related information, advice and representation they need to resolve their problems. Could a new approach to Public Legal Education, delivered by youth workers, help to reach young people in their communities and in doing so to empower them to understand and use the law?

In 2016, the Legal Education Foundation together with the Esmee Fairbairn Foundation awarded a multi-year grant to leading UK charity Youth Access to deliver an innovative programme of public legal education and social action, working with young people in three locations across England. Experts in research on child and adolescent mental health from the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families were recruited to conduct a process evaluation of the programme, which can be downloaded here.

Youth Access coordinates a national network of organisations that deliver advice, information and counselling to young people aged sixteen to twenty-five. The programme is entitled Make Our Rights Reality (“MORR”) and aims to empower vulnerable young people aged 15 to 25 to act as a force for change in society and use the law as a tool for tackling the everyday problems that they experience. Through inspiring young people to participate in social action and Public Legal Education (“PLE”) training to increase their legal capability, the programme aims to encourage young people to engage meaningfully in civil society and to exercise their rights and responsibilities as emerging adult citizens.

Why evaluate?

Youth Access have a long history of championing the use of evidence in the sector, and have worked with researchers and evaluators on a number of their projects. They are wholly committed to delivering evidence based programmes that support vulnerable young people to secure their rights, protections and fair treatment. The programme designed by Youth Access was both novel and experimental, and as such, everyone involved in the project was keen to understand how it would work in practice. It was decided that a realistic process evaluation approach should be adopted, to enable all stakeholders to understand how the programme operated in practice, and in particular to better understand the ways in which young people engaged with and moved through the programme.

What is a realistic process evaluation?

Realist evaluation is designed to improve understanding of how and why interventions work or do not work in particular contexts (Westhorp, 2014). A process evaluation is: ” a study which aims to understand the functioning of an intervention by examining implementation, mechanisms of impact and contextual factors” (Moore et al. 2015) It is complementary to, not a substitute for, high-quality outcomes or impact evaluation (using methods such as a Randomised Control Trial- see this comprehensive guide from J-Pal for further information).

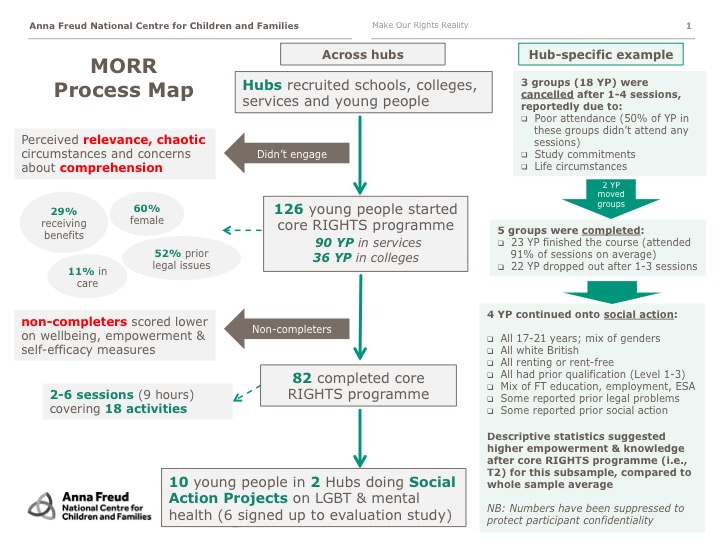

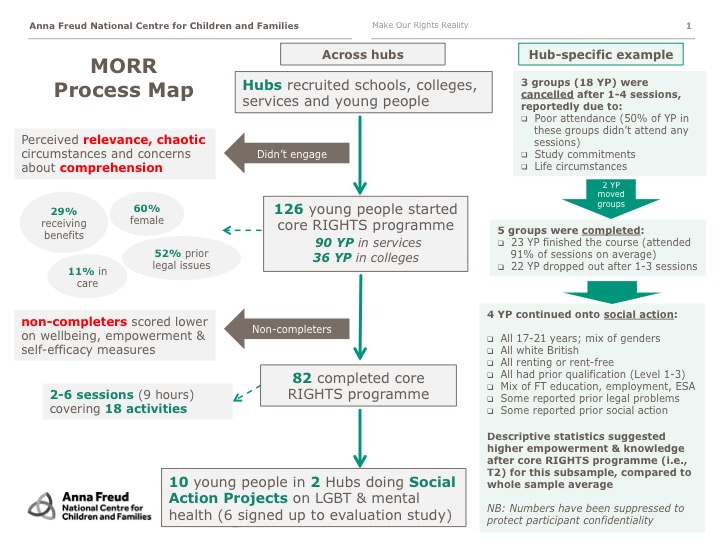

We commissioned academics at the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families to help us to gain a better understanding of: 1) Who engages with the programme and how 2) What the core rights training looked like 3) What the social action projects looked like and 4)Whether there was evidence to suggest the rights training was successful on its own terms. An additional aim was to suggest a research strategy for evaluating the impact of the programme (or parts of the programme) on outcomes for young people. We also asked the evaluators to produce a process map for the programme, to visually present the way in which young people engaged with the programme (see figure below).

Map summarising the way young people engaged with and moved through the Make Our Rights Reality Programme.

Key lessons from the evaluation

1) Who engages with the programme and how?

Hub facilitators recruited young people through three main sources: 1) young people currently engaged with services delivering the programme (n = 37), 2) young people in other organisations/groups (e.g., LGBT groups, care leavers) not delivering the MORR programme (n =30), 3) mixed groups of both current service users and non- service users (n =15), and 4) young people in education settings where training was delivered in schools to classes of students (n=42) (n = 2 missing).Of the 126 young people who took part, 60% were female, 52% had prior legal issues in the past twelve months, 29% were in receipt of benefits and 11% were in care or another institution. Of these 126 young people who started the core training, 82 completed the core training (65% completion rate). Young people were more likely to complete the course if they had higher levels of well-being or self-efficacy at the start of the course. Young people were less likely to engage in the course, and more likely to exit early, if they did not perceive it as relevant to their daily life (i.e., they had no prior or current experience of legal rights issues), if they had chaotic life circumstances and if they were concerned about being able to comprehend the course). As anticipated, in the timescale of the evaluation few hubs had full social action projects in progress but in interviews and focus groups, young people expressed enthusiasm for taking part in social action projects in general and there was evidence of use of informal social action (see 3 below). Still, young people in interviews suggested 2 areas of interest for future projects, including reaching out to young people in schools and colleges to teach them about rights-based issues, working with service commissioners and campaigning.

2) What did the core rights training look like?

The core training programme involved 9 hours of 18 modules delivered in 2-5 sessions in a group format of 4- 12 young people. Facilitators adhered to the core training manual according to observations and interviews in general but adapted the material in three ways: 1) handouts were condensed or restructured, 2) the order or activities was changed and 3) the pace of activities was altered. Facilitators reported that these adaptations were essential to meet the needs of young people in the groups, and young people reported that the flexible format of the course was very important to ensure it was comprehended by all participants (e.g., by repeating content that was not initially understood).

3) What did the social action projects look like?

In the timescale of the evaluation, social action projects were fully underway in two hubs, related to LGBT and mental health. Twenty young people described in interviews and focus groups more informal social action pathways, ranging from providing advice and support to friends and family about rights-based issues to informing ongoing social action activity they were involved in. For example, one young person had set up a group for young people involved in probation services since being involved in MORR.

4) Was there evidence to suggest the rights training was successful on its own terms?

On average, young people remembered 77% of the six RIGHTS. The highest average score for the eight knowledge based questions asked at the end of the programme related to how to act if stopped and searched by the police (almost 90%). When examining those young people with complete data at T1 and T2 (n=64), mean levels of wellbeing, empowerment and self-efficacy significantly increased from T1 to T2. The sub-group analysis of young people with complete data at T1 and T2 by education (n=27) vs. non-education (n=37) setting revealed that, while increases in wellbeing, empowerment or self-efficacy for young people taking part in MORR in education settings were not statistically significant, we observed significant increases in all three domains when young people took part in MORR in non-education settings. Thus young people recruited from outside of formal education settings benefited more than those participating in formal education settings. However, these differences could be due to a lack of power in the education setting as there was less data, or because those taking part in the education setting perceived the material as less relevant to them as they were less likely to have prior experience of legal- rights issues. Moreover, the findings could also be due to other activity young people were taking part in through the hubs, however young people recruited through hubs included former service users or those recruited from groups or services (e.g., LGBT groups, care leavers) not part of services delivered by the hubs. Given the sample sizes, further sub-group analyses of young people with complete data at T1 and T2 taking part in non-education settings (e.g., service users vs. non-service users) were not possible.

Reflections and next steps

One of the key issues facing Youth Access in the first year of MORR was recruitment of young people to the programme- the programme was initially designed to be delivered outside of formal educational settings, but issues in securing participants led to facilitators expanding the programme to schools and colleges. The findings of the evaluators indicate that young people who participated in the programme in a formal educational setting did not benefit from the training in the same way that young people who participated through the hubs did. In the next year of the programme, steps will be taken to target the course at individuals outside of school settings.

One challenge for the programme is understanding how to keep young people with lower levels of well being and confidence engaged. These are the young people who can be said to need the training provided the most, but the evaluation indicated that young people with lower levels of well-being and self-efficacy were less likely to complete the course.

One important finding which has broader implications for Public Legal Education in general is that young people were more likely to engage when they perceived the course content as relevant to their daily lives. This strengthens arguments that Public Legal Education is best delivered on a “just-in-time” basis, at the point at which young people are experiencing or likely to experience legal problems.

The Legal Education Foundation and the Esmee Fairbairn Foundation are excited to continue working with Youth Access as the programme moves into year two. For more information about the programme please visit the Youth Access website.